Iraq is grappling with a growing crisis as climate change and water scarcity fuel a surge in environmental migration. Harry Istepanian delves into how the agricultural sector, consuming 85% of the country’s water, is crippled by systemic inefficiencies, droughts, and conflict. These factors have displaced thousands, particularly in southern Iraq, forcing communities to abandon their homes and livelihoods. As many seek refuge in urban slums, the lack of government support and rising poverty exacerbate the situation. Despite the dire circumstances, Istepanian highlights the hope for return, as displaced Iraqis express willingness to resume their agricultural lives if water availability improves.

While the impacts of climate change mainly focus on food security, health, and the economy, many other critical issues remain underreported, including the pressing matter of “environmental migration.” Environmental migration in Iraq refers to the displacement of communities due to environmental changes caused by climate shifts. In recent years, the link between climate change and migration patterns has become more apparent. A study by the International Centre for Migration Policy Development highlighted the close relationship between climate change and human mobility, describing them as “two sides of the same coin.” The Director of the International Organization for Migration IOM) emphasized, “We have officially entered the era of climate migration.”

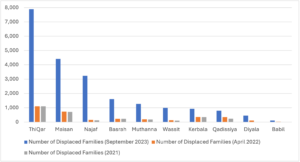

In 2023 alone, climate change displaced tens of thousands of Iraqi families, particularly in regions suffering from drought, desertification, and water scarcity. This marked a significant increase compared to previous years, as reported by various local and international organizations including IOM. As of October 2023, the IOM estimates upwards of 130,000 Iraqis in the south have been displaced due to climate change, jumping from approximately 80,000 as of August 2023. Projections suggest that climate change could force even more Iraqis to migrate internally by 2050, primarily due to worsening environmental conditions.

(Source: IOM)

Why is migration linked to climate change in Iraq?

In Iraq, climate change contributes to migration in both direct and indirect ways. Severe environmental events like droughts have compelled people to relocate. Additionally, indirect effects such as reduced water availability, declining agricultural yields, and the loss of livelihoods have made it increasingly difficult for communities, especially in rural areas of the southern governorates and middle Euphrates, to sustain themselves, prompting them to seek better living conditions elsewhere.

Environmental displacement in Iraq involved those forced to leave their homes due to sudden or gradual environmental changes that severely impacted their lives. This displacement in most cases was permanent. Vulnerable groups, such as internally displaced persons and communities in impoverished regions of the marshes, are particularly at risk, as they often reside in areas most affected by climate change and lack the resources to adapt or relocate easily.

Water Scarcity Devastates Iraq’s Agriculture and Rural Communities

The future of climate-induced migration in Iraq appears concerning, given the predictions from international and local organizations. One of the most evident impacts of climate-induced migration in Iraq is due to the increasing frequency and severity of droughts. The Iraqi government reports that average annual rainfall has become less predictable since the 1970s and has declined by 10% over the past two decades. Experts project that by 2050, precipitation in Iraq will decrease by 25% compared to pre-2000 levels, further intensifying desertification and water scarcity.

Iraq’s agricultural sector, which consumes 85% of the country’s water, is severely impacted by water scarcity, with only about 40% of water reaching farmers due to salt infiltration and system leakages. The southern and central regions rely on river irrigation, while the northeast depends on rainfall. However, recent droughts and conflicts have destroyed irrigation systems, leading to crop and livestock losses, especially in northern Iraq.

In southern Iraq, prolonged water scarcity and pollution have left millions affected. Traditional flood irrigation wastes water, and despite the need for sustainable practices like drip irrigation, governmental neglect hampers progress. Many rural farmers face crop failures, animal diseases, and economic hardship, with some forced to rely on expensive or contaminated water.

These indicators underscore the urgent need for expanded efforts to combat climate-induced migration in Iraq. This issue goes beyond geographic movement—it is a humanitarian crisis marked by suffering, challenges, and stories that deserve attention. It highlights the gaps in human rights protection, social and climate justice, and the harsh realities faced by marginalized and vulnerable populations in Iraq’s most climate-affected regions.

Water scarcity disproportionately affects poorer communities, leading to severe health issues, such as the 2019 Basra water crisis where over 118,000 people were hospitalized due to contaminated water. The government has restricted certain crops and reduced cultivation areas, but this has led to livelihood losses for many farmers. To cope, agricultural workers seek food assistance and drought-tolerant seeds.

The seawater tide leaves behind a white crust on anything that it touches, a testament to its salt density. Photo © IOM Iraq 2023/Raber Aziz

The U.S.-led coalition invaded Iraq on March 20, 2003, and withdrew in 2011. The conflict resulted in an estimated half a million Iraqi deaths, displaced at least 9.2 million people, and left over 4.7 million individuals facing moderate to severe food insecurity. Governorates including Ninawah, Salahudin, and Diyalah were particularly affected by conflict-driven displacement, while southern Iraq governorates including Maissan, DhiQar, and Basrah face displacement due to environmental factors.

Farmers, primarily reliant on crops and livestock, face income losses due to water scarcity. High costs of clean water, lack of modern irrigation techniques, and rising food prices exacerbate poverty, particularly in southern and western Iraq. Many farmers resort to temporary or permanent migration as a survival strategy. Some adopt coping measures like changing crops, digging wells, and selling property, but financial constraints limit the majority’s ability to adapt effectively. Attachment to land and lack of resources prevent some from migrating, despite severe hardships. Social networks, particularly tribal connections, play a crucial role in facilitating migration and finding opportunities elsewhere. The lack of agricultural employment opportunities drives young people to migrate, often resulting in entire families following once new opportunities are found.

These issues highlight the complex interplay of environmental challenges, economic struggles, and social dynamics driving displacement in Iraq. The IDMC and NRC suggest that migration in Iraq could accelerate due to the “cumulative causation of migration” phenomenon, where the departure of others creates a psychological push for more to leave, as staying becomes harder to justify. Despite this, many migrants expressed a willingness to return if water availability improves, enabling them to resume agricultural work.

To address the looming crisis of environmental migration in Iraq, a multi-pronged approach is essential. This includes implementing sustainable water management practices, investing in climate-resilient agriculture, and enhancing support for displaced communities. Collaborative efforts between the government, international organizations, and local stakeholders are necessary to ensure that those affected by climate change can rebuild their lives with dignity. While challenges remain immense, fostering resilience through targeted interventions offers a pathway toward mitigating the crisis and ensuring a sustainable future for Iraq’s most vulnerable populations.

Harry Istepanian is a PMP certified, independent Chartered Engineer (CEng.) with more than 30 years of experience in large-scale power and water utility and IWPP projects in developing countries, including SE Asia and MENA in addition to New Zealand and Australia.

![Iraq Climate Change Center [IC3+]](https://iraqclimatechange.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/logo2.png)